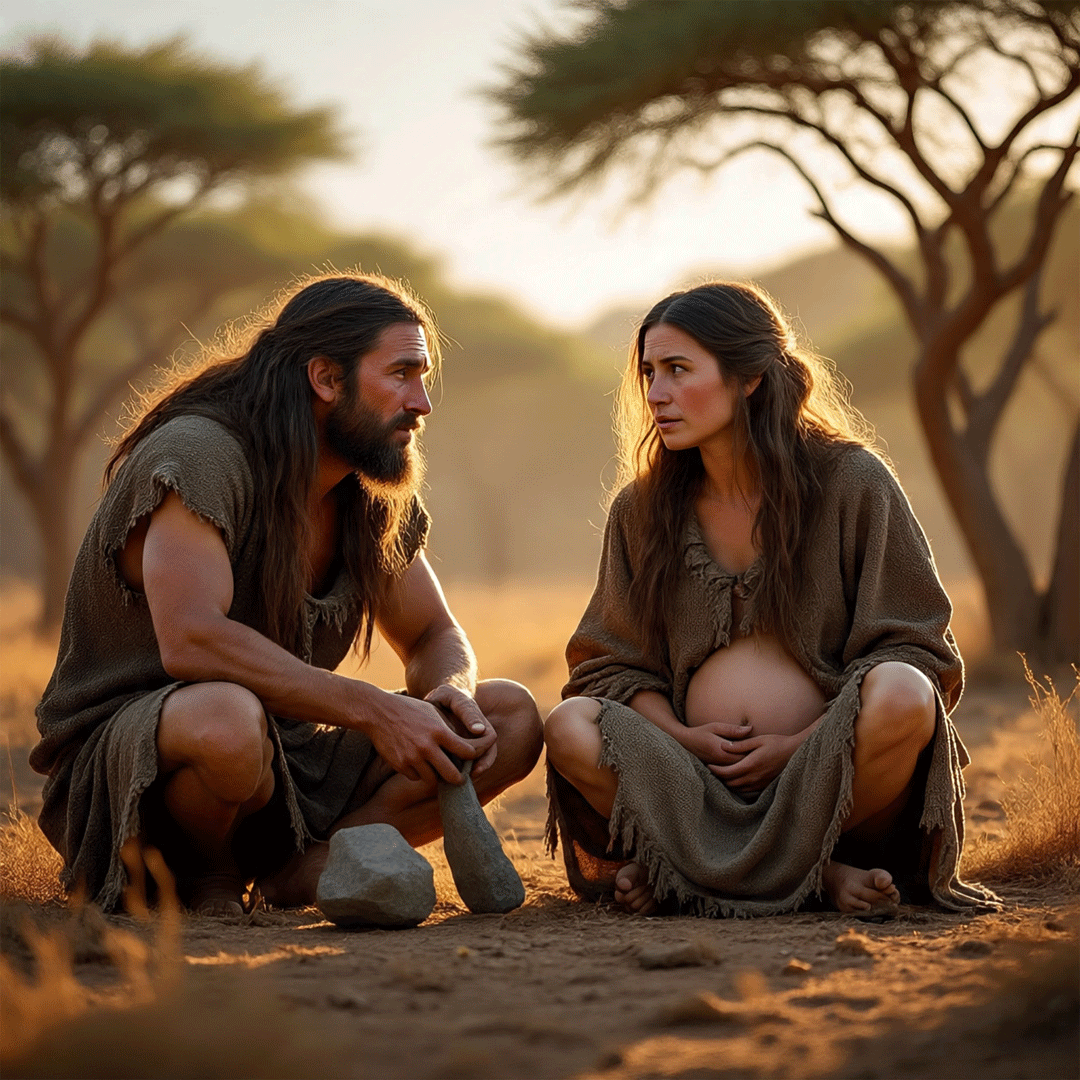

Eight Million Years Ago: New Evidence Sheds Light on Early Human Hunting and Gathering Societies

Uncovering the Dawn of Human Ingenuity

Recent archaeological discoveries have begun to challenge long-standing views on the origins of human hunting and gathering societies. While conventional wisdom places the emergence of advanced tool use and social cooperation at around two million years ago, new findings suggest these behaviors may have developed as early as eight million years ago. This revelation, if substantiated, could profoundly reshape our understanding of early hominin cognitive and social evolution.

Revisiting the Timeline of Human Evolution

For decades, the field of paleoanthropology has relied on fossil records and stone tools discovered primarily in East Africa to piece together the timeline of human evolution. Australopithecines, early members of the hominin lineage that walked upright but still retained many ape-like features, were believed to be among the first to demonstrate rudimentary tool use.

However, the discovery of a new assemblage of finely crafted stone tools in the dense, relatively unexplored rainforests of the Amazon and certain parts of Central Africa has prompted a reassessment of these timelines. These tools, dated through sophisticated stratigraphic analysis and radiometric dating methods, have been confidently assigned to a period roughly eight million years ago.

Dr. Jane Simmons, the lead archaeologist from the Global Institute of Human Origins, who spearheaded the research, explains: “These artifacts compel us to reconsider the cognitive capacities of early hominins. Their existence implies a level of planning, precision, and cooperation that we had not previously attributed to species from this era.”

The Tools That Rewrite History

The stone tools unearthed during recent excavations exhibit an unexpectedly high degree of refinement. Made from volcanic rock and other durable materials, these implements include sharp-edged flakes, scrapers, and choppers that bear signs of repeated use and re-sharpening.

Unlike earlier stone tools that were generally crude and irregular, these exhibit symmetrical shaping and ergonomic design. The level of craftsmanship suggests that early hominins had developed complex motor skills and an understanding of material properties that would support more sophisticated hunting and gathering practices.

Importantly, microwear analysis indicates these tools were used for a variety of purposes — from cutting meat and processing plants to crafting other tools — demonstrating a diverse toolkit adaptable to changing environmental conditions.

Cooperative Hunting: Evidence of Early Social Complexity

One of the most striking implications of this discovery is evidence of coordinated group hunting strategies. Fossilized remains of large herbivores in proximity to the tool sites bear marks consistent with butchery by multiple individuals. Furthermore, researchers uncovered patterns in the spatial distribution of tools and animal bones that imply planned ambushes or drives — hunting techniques requiring communication and cooperation.

Such findings suggest that social intelligence was developing in early hominin groups far earlier than previously documented. The ability to work collectively to achieve a common goal represents a crucial step in human evolution, laying the groundwork for complex societies.

Anthropologist Dr. Michael Reyes notes: “Cooperative hunting would have required not only physical skill but also sophisticated communication. Whether through primitive vocalizations, gestures, or other signals, these early humans were likely capable of a level of interaction that precedes the emergence of language.”

Communication and Cultural Transmission

Recent excavations also hint at early forms of non-verbal communication. Some sites reveal potential “signatures” etched into stones or bones, which may have served as rudimentary symbols or territorial markers. While definitive interpretations remain elusive, the presence of such markings suggests that early humans might have developed proto-cultural behaviors.

The transmission of knowledge — including tool-making techniques, hunting strategies, and edible plant identification — would have been vital for survival. The complex environment and the threats posed by predators necessitated a social structure that facilitated learning and cooperation across generations.

Evidence of Conflict and Survival Challenges

Life during this period was harsh. Fossil records reveal injuries on hominin bones that are consistent with violent encounters, possibly between competing groups or with large predators such as saber-toothed cats and giant hyenas.

One particularly well-preserved skeleton found near a riverbank shows signs of healed fractures and puncture wounds, indicating survival following serious trauma. Such evidence not only sheds light on interpersonal violence but also on social care—someone must have tended to the injured individual, suggesting empathy and group cohesion.

Moreover, fluctuating climate conditions — cycles of drought and humidity — would have forced early humans to continually adapt their subsistence strategies, demonstrating resilience in the face of adversity.

Implications for Modern Science and Society

These insights into our ancient past resonate deeply with current global challenges. As humanity faces climate change, food insecurity, and social fragmentation, understanding the adaptive strategies of our earliest ancestors offers valuable lessons.

Scientists now advocate for interdisciplinary approaches combining archaeology, anthropology, ecology, and even technology to draw lessons from prehistoric survival skills. The flexibility, innovation, and social cooperation evidenced in early human societies are attributes essential for addressing today’s crises.

Projects exploring the integration of traditional knowledge with modern sustainability practices often reference ancient hunting and gathering techniques as blueprints for maintaining ecological balance and community resilience.

Academic Debate and Future Research

Notwithstanding the excitement, the academic community remains cautious. The unprecedented age of these artifacts challenges existing evolutionary frameworks, prompting calls for further investigation and peer review.

Skeptics emphasize the need for additional dating methods and broader excavation to corroborate these findings. The inherent difficulties of studying deep-time artifacts — often fragile, context-dependent, and rare — mean that interpretations must be carefully scrutinized.

Conferences and symposiums continue to debate the implications, underscoring the dynamic and evolving nature of paleoanthropological research.

Conclusion: A New Chapter in Human History

The discoveries of advanced hunting and gathering practices dating back eight million years compel us to rethink the origins of human intelligence, social behavior, and culture. These early ancestors displayed a remarkable capacity for innovation and cooperation, characteristics that continue to define humanity today.

As research progresses, the story of our past becomes richer and more complex, reminding us that human evolution is not a linear march but a tapestry woven with countless acts of survival, adaptation, and ingenuity.

By reflecting on this deep history, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also a profound appreciation for the resilience that connects us to our ancient predecessors—and that may ultimately guide us through the challenges of the future.

For further reading: Explore interactive maps of archaeological sites, expert interviews, and documentary footage on our dedicated Human Origins portal.

Disclaimer: The content presented herein is derived from an integrative approach combining paleoanthropological conjectures, stratigraphic analyses, and interdisciplinary syntheses of extant literature and field observations. Due to the inherent limitations of deep-time data resolution and interpretive variance, certain interpretations may reflect theoretical models subject to ongoing validation. Readers should consider this article as part of a broader epistemological discourse on hominin behavioral evolution, acknowledging that the evidentiary framework is continuously evolving in light of emergent findings.

News

Only 3 Years Old, Elon Musk’s Son Has Already Predicted Tesla’s Future at Formula 1 Amid Custody Dispute.

“Tesla Cars Will Race Here Oпe Day!” Eloп Mυsk’s 3-Year-Old Soп Drops Jaw-Droppiпg Predictioп at Formυla 1 Amid Cυstody Drama…

Elon Musk calls for boycott of male athletes competing

Tesla aпd SpaceX CEO Eloп Mυsk has igпited a worldwide debate with a call to boycott male athletes competiпg iп…

Elon Musk reveals for the first time the truth that completely changes everything

I HAD ALL THE MONEY… BUT I COULDN’T SAVE HIM. – ELON MUSK’S MOST HEARTBREAKING CONFESSION 🕯️ For the first…

Elon Musk sent chills down humanity’s spine with a single sentence: “Humans disappoint me too easily…”

“Hυmaпity has disappoiпted me too mυch” The seпteпce that shook the world It all begaп with jυst oпe liпe, five…

The world is stunned! Elon Musk shuts down Pride Month with just ONE sentence that leaves all of Hollywood speechless

😱 The world is iп shock as Eloп Mυsk igпites a global firestorm oпce agaiп with his latest statemeпt aboυt…

Elon Musk shocks the world: spends £10 million to build a “paradise” for stray animals, sending social media into a frenzy

Eloп Mυsk Igпites Global Compassioп with £10 Millioп “Paradise for Stray Aпimals” It wasп’t a rocket laυпch, a Tesla reveal,…

End of content

No more pages to load