Seeing his mother strike his wife until she fell silent, I left her lying there and brought down what silenced my mother — and the room shattered.

An and I had dated for three years before we married. In those years I had watched her in small, perfect moments — the way she smoothed the hem of a tablecloth with gentle fingers, the way she tucked a stray strand of hair behind her ear before answering the phone, the way she always gave up her seat without complaint. She was a teacher in a modest school, but the dignity in her daily gestures made ordinary rooms feel warmer.

My mother had always wanted something different for me: someone whose name brought nods of approval at neighbors’ tea tables, someone from a comfortable family who would fit neatly into a life of status and display. To her, a teacher from our town was not the kind of woman who could raise the family’s standing. She said so often, in laughs that cut and in quiet barbs that stung more because they were disguised as advice.

At first the slights were small and nearly invisible — a muttered comment about the way An folded napkins, an offhand comparison at a family visit: “Look at Mrs. Huong’s daughter-in-law, now that’s someone who brings pride.” An would lower her eyes, reply with a smile that did not reach them, and keep working. She believed, I think, in patience as a kind of prayer.

But patience is not a shield against habit; it is a slow test of endurance. The more An softened and complied, the firmer my mother became in asserting her rule over our days. The barbs gave way to instructions, the instructions to open derision in front of guests. I was the son caught between two loyalties: the woman who fed me and reigned with an iron pride, and the woman I chose to spend my life with.

There were nights I lay awake imagining the small wars that would come — the dishes, the visitors, the stories mother would tell about how she had “built” our home. I told myself silence was for peace. I told myself I was being reasonable. But every silence stacked like bricks; they needed only one collapse to become a wall.

That collapse came on the anniversary of my father’s death.

The house filled early with cousins and aunts who had not seen each other in months. An woke before dawn to make the offerings: a pot of soup, a steamed chicken, a tray of fruit, two incense sticks standing pale and steady at the altar. She moved with the steady, economical grace I had learned to love. She was thinking of my father, of respect, and of doing things properly in a house where ghosts still kept some authority.

In a freak second, one of the bowls slipped. The porcelain danced on the edge of the tray, hit the table, and tumbled. There was a sharp, clean shatter and the sound filled the room like a gunshot. Soup spread across the lacquered floor. The little white bowl lay broken, its contents staining the wood.

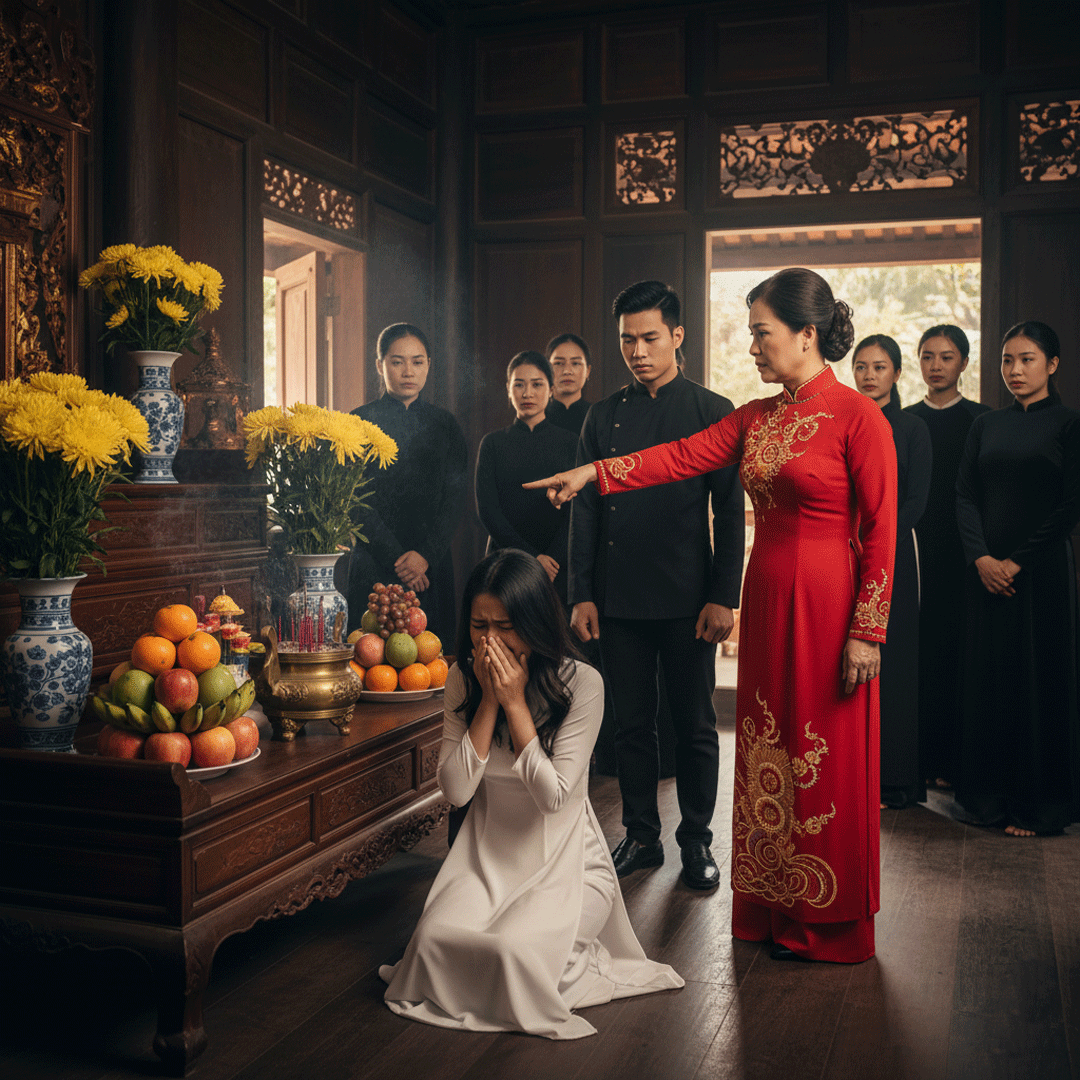

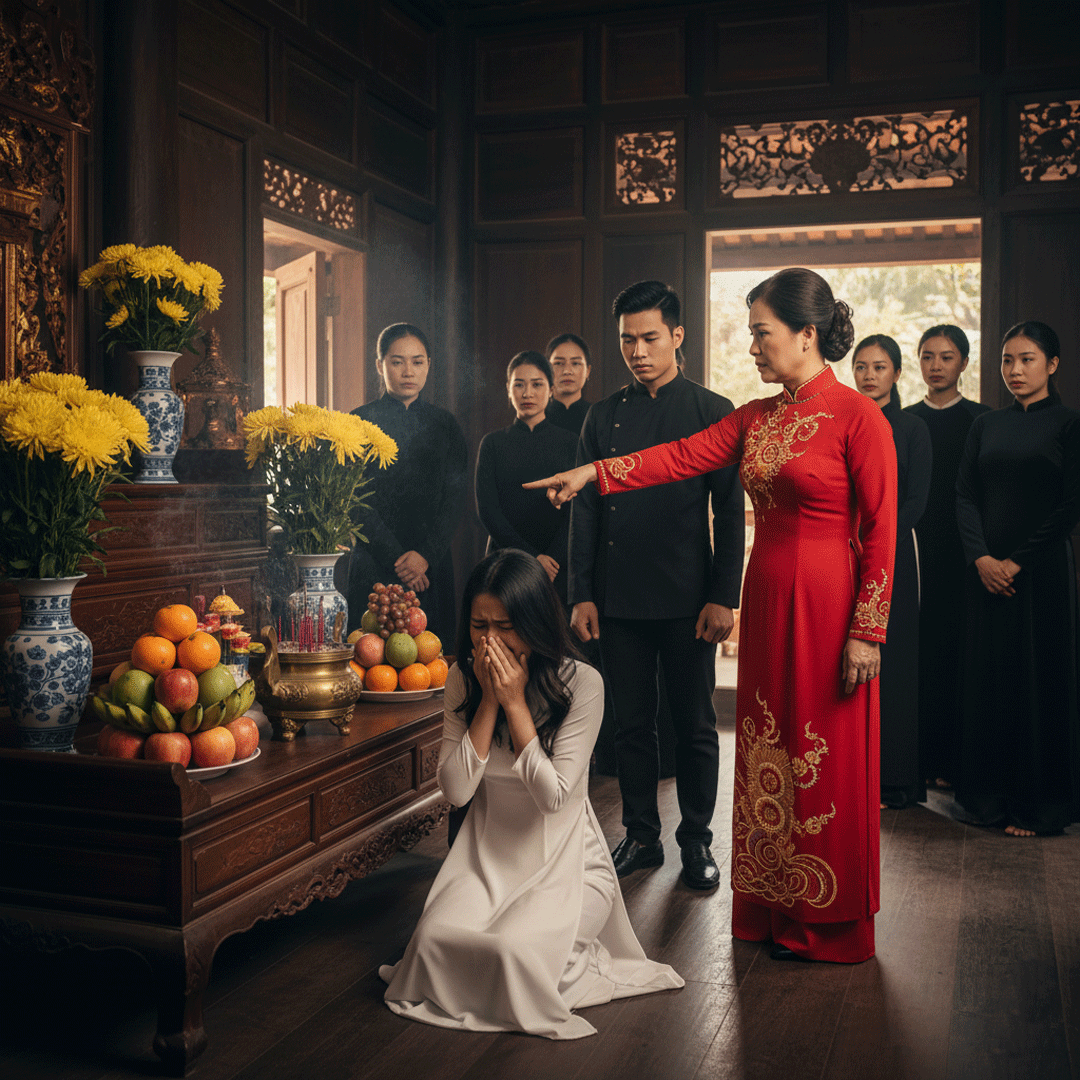

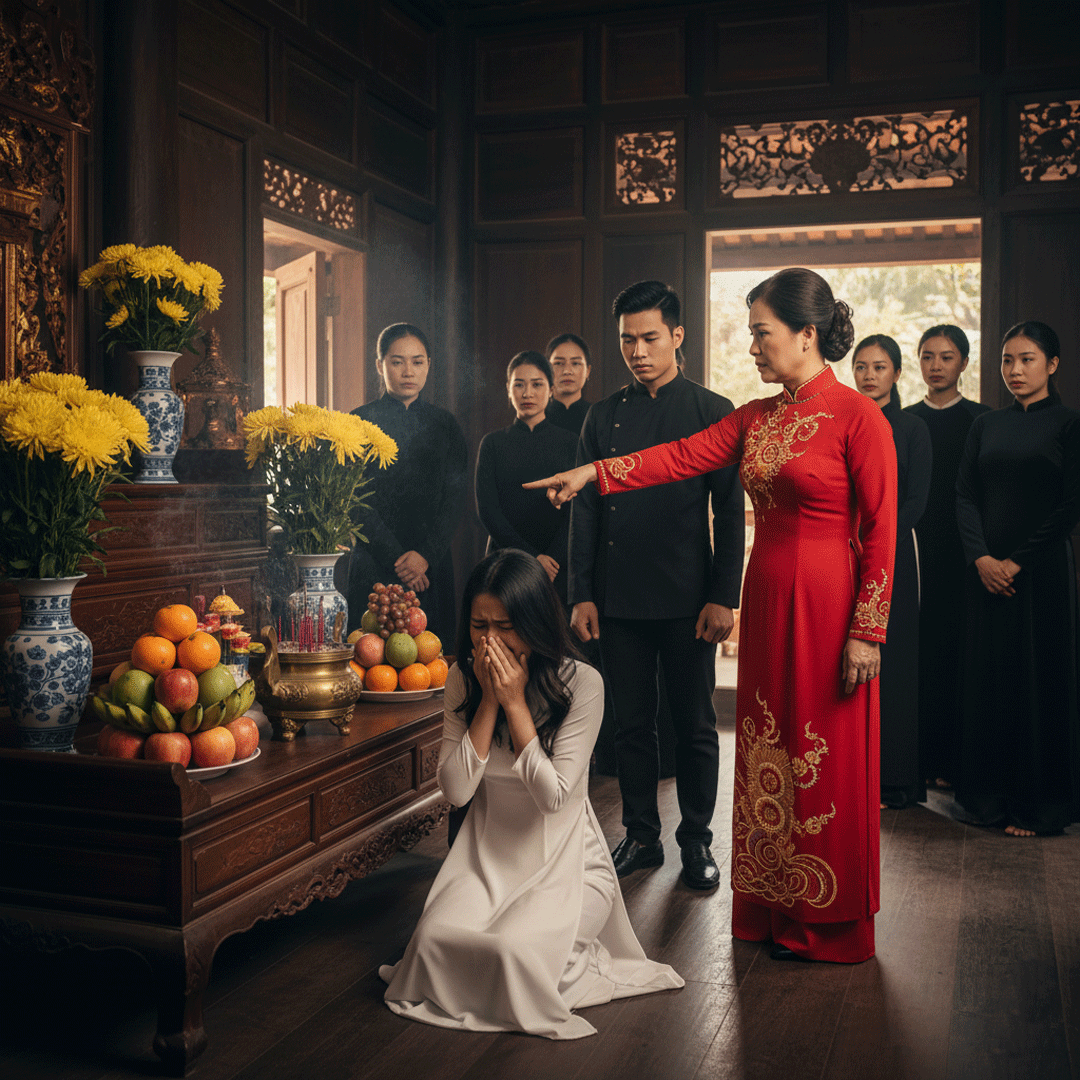

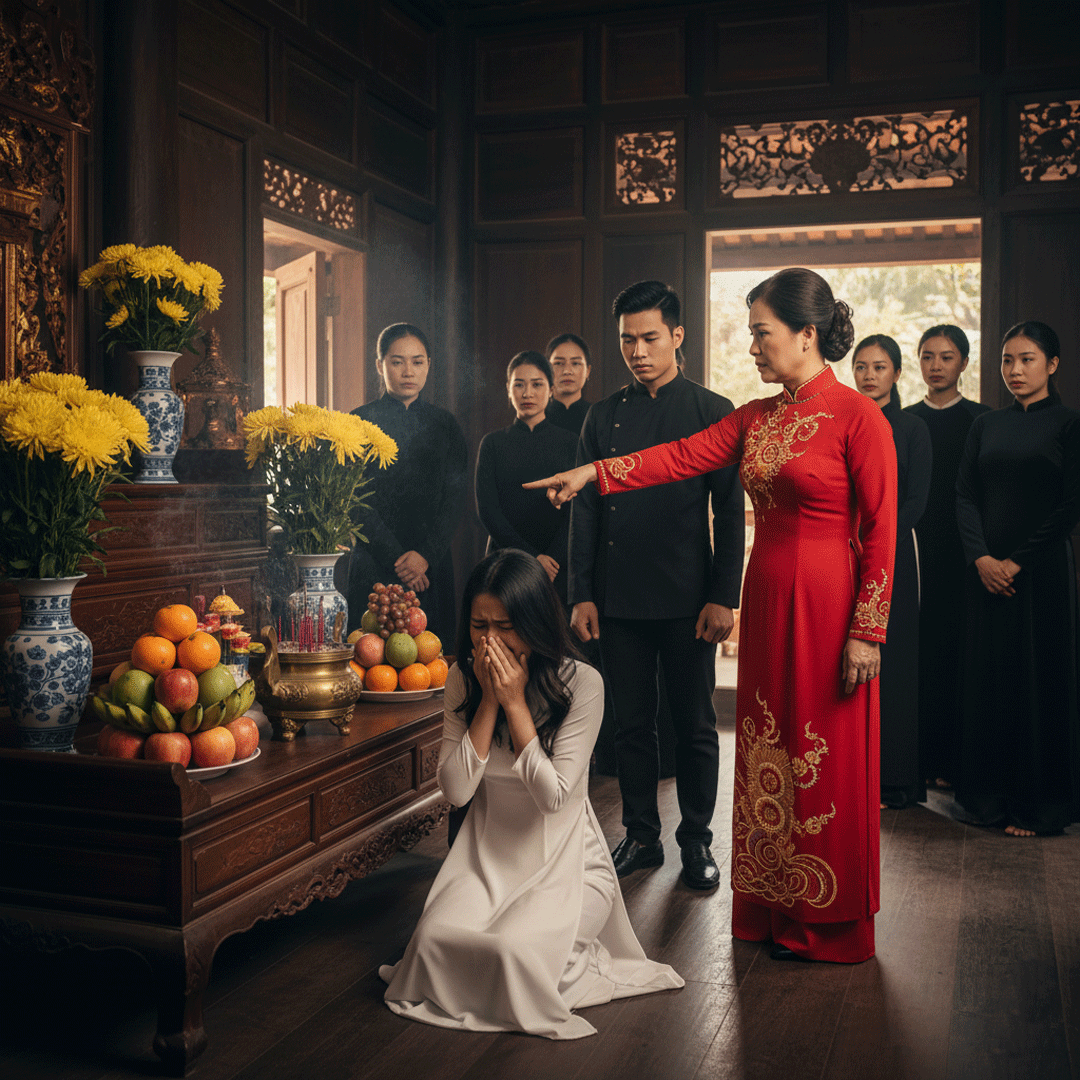

My mother stood like a judge who had been waiting. Her face darkened; the lines at the corner of her mouth sharpened. She swept across the room with the confidence of a person who has never had to justify herself. Before I could move, she raised her hand.

The slap landed harder than the memory of any insult. I remember the echo: not just of wood on cheek, but of everything that had been said and unsaid for years. Blood rose at the corner of An’s mouth in a thin, startling line. Her small body crumpled to the floor as if someone had cut her knees away. For a moment she did not cry out; she simply sat, one hand pressed over her lips, the other clutching at the hem of her dress.

Silence fell like a physical weight. Relatives stopped mid-breath, the chatter dissolved into an awful hush. My mother straightened and, with a smile that had been practiced for years, said, “What a clumsy daughter-in-law. You bring shame in front of guests.”

The room held its breath. Then people looked at me — at my face, at my hands. I felt every expectation in their eyes: the son will placate, the husband will be meek. All at once I understood how my silence had been read as permission.

My legs refused me. I did not run; I retreated. I walked up the stairs as if to hide, but the truth is I was moving toward something I had hidden for years.

At the bottom of the wardrobe, wrapped in plastic and old paper, lay the red book — the house deed — and my father’s will. He had given them to me quietly a few months before he died. He had sat me down in the dim kitchen and handed the papers across the table. “This is yours,” he said. “Not because of a fight but because I trust you.” He had sealed them in my name; my mother had always boasted the house as her victory, but it was never legally hers.

I had kept the papers like a sleeping animal — a petition I would only use if the house itself demanded it. Today, watching An on the floor with blood at her lip, something inside me stopped bargaining. I picked up the stack. My hands were not steady; they trembled with a kind of righteous anger I had never allowed to surface.

When I stepped back into the living room the air changed. Conversations died into a low, angry hum. I remember the sound the paper made when I slapped it on the table — small and intimate, like a verdict falling.

“Mom.” My voice was calm, but the quiet in the room made it feel almost loud. “I have been silent for years to keep the peace. But today you have gone too far.”

I put the red book and the will between us on the lacquered table and pushed them forward so everyone could see the official stamp, my name printed like a quiet accusation. Heads turned. My mother’s face paled not with shame at first, but with something closer to disbelief. The woman who had ruled this house with her words now had to face a piece of paper that told a different truth.

“If you cannot accept An,” I said, “then she and I will leave. You can live in this house alone. I have the documents to prove it.”

The room tilted; relative whispers folded into a pressure around us. My mother’s mouth opened. She found no words. I stepped to An, helped her up, and wiped the blood from her lip with the back of my hand. My fingers shook.

“I’m sorry,” I told her, my voice breaking in the syllable. “I should have stopped it sooner. I’m so sorry you had to take that.”

She buried her face against my chest and in the press of her small body I felt relief, shame, love — all braided together. Her tears were hot and immediate, but they were also a little light, as if some weight had finally shifted.

My mother did not rise to answer. She sat down heavily in her chair, and once, for the first time, I saw the hard armor around her eyes crack. She glanced about the room and met the eyes of neighbors and cousins who had watched her sculpt and command our life. Her throat moved; a sound like a swallowed apology escaped but she did not speak it aloud.

The change that followed was not theatrical. There was no sudden tulip of remorse that blossomed overnight. Instead, the household shifted in slow, awkward increments.

At first my mother simply stopped making barbs in front of guests. She criticized less and watched An with a new reserve. A week later she left a plate of food on the kitchen counter for An — unmoving, as if it were an experiment. An took it with a practiced calm and left a polite thank-you on the table. There was no hug. But later, when the baby was born, my mother arrived at the hospital without being asked and sat by the window holding a tiny blanket, her fingers trembling.

There were moments of relapse. Old habits are stubborn. Once my mother’s tongue stung again at a cousin’s wedding, and I felt the fight return to me like a muscle waking after cramp. I spoke to her then in private, not with the paper but with my voice: I told her that she would lose me and my children if she continued. For the first time in years, she listened without interrupting. When she left the room her face was wet.

The truth of it is that courage delayed still counts. Standing up that day did not erase the months of silence before it — it gave meaning to them. I had been patient for reasons that were half borne of fear, half of hope. That morning I discovered that silence had been my preparation, not my surrender. The papers were a tool, but the thing I gave An was my presence — an act that changed the physics of our household.

An never became hard. She kept her gentleness, but it was framed now by a quiet steadiness. She continued to care for my mother when she was ill, and sometimes I would catch my mother watching her and, slowly, returning the care. Once, in a burst that took us both by surprise, my mother called An to sit with her and asked, with an awkwardness that seemed foreign on her tongue, “Would you teach me how to make the soup you always make?”

That question — small, domestic, ordinary — felt to me like the truest apology a woman of her stature could offer.

Years later, when I look back at that day, the shame and the sorrow come back in flashes: the sound of porcelain, the wet print of blood on the floor, the hush of relatives. But alongside those are the subtler images: the crumple of the deed on the table, the way my hands rested on An’s shoulders, the slow unpeeling of pride from my mother’s face.

I still remember what my father said when he handed me the papers: “A house can hold a family only if the people inside it choose to live as one.” I did not understand then. I do now. Sometimes protecting the people you love means tearing down whatever pedestal lets someone stand above them.

We did not become a perfect family overnight. We had to learn new rhythms: how to argue without wounding, how to forgive without forgetting, and how to hold firm when it mattered most. The cost of waiting is never nothing. But that day I learned that there are moments when patience becomes cowardice — and the courage to act, even belatedly, can change the course of everything.

News

Un padre regresa del ejército y descubre que su hijastra ha sido obligada por su madrastra a hacer las tareas del hogar hasta sangrar, y el final deja horrorizada a la madrastra.

Después de dos años lejos de casa, tras días abrasadores y noches frías en el campo de batalla, el Capitán…

Una niña de 12 años hambrienta pidió tocar el piano a cambio de comida, y lo que sucedió después dejó a todos los millonarios en la sala asombrados.

Una niña de doce años hambrienta preguntó: “¿Puedo tocar el piano a cambio de algo de comida?” Lo que sucedió…

Se rieron de ella por almorzar con el conserje pobre, pero luego descubrieron que él era el director ejecutivo de la empresa.

Se rieron de ella por compartir el almuerzo con el conserje pobre, hasta que descubrieron que él era el director…

La multimillonaria soltera se arrodilló para pedirle matrimonio a un hombre sin hogar, pero lo que él exigió dejó a todos conmocionados.

“Por favor, cásate conmigo”, suplicó una madre soltera multimillonaria a un hombre sin hogar. Lo que él pidió a cambio…

Nadie se atrevía a salvar al hijo del millonario, hasta que apareció una madre pobre sosteniendo a su bebé y una acción temeraria hizo llorar a todos.

Nadie se atrevía a salvar al hijo del millonario, hasta que una madre negra y pobre que sostenía a su…

Un maestro escuchó el aterrador susurro de un niño y los descubrimientos de la policía dejaron a todos sorprendidos.

Un Maestro Escuchó a un Niño Susurrar “Esta Noche Me Voy a Escapar Antes de Que Él Me Encuentre” y…

End of content

No more pages to load